An extraordinary journey and an astonishing discovery

Recorded by the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas in his famous work, History of the Indies, Christopher Columbus’ testimony, crossed by an easily perceptible emotional crescendo, shows that the nights preceding August 16, 1498 announced the arrival of a crucial moment of his third expedition into the New World:

And he says each night he was marveling at such a change in the heavens, and of the temperature there, so near the equinoctial line, which he experienced in all this voyage, after having found land; especially the sun being in Leo, where, as has been told, in the mornings a loose gown was worn, and where the people of that place - Gracia - were actually whiter than the people who have been seen in the Indies.1

Everything on that day, August 16, heralded that something extraordinary was going to happen. After sailing more than 26 leagues on a sea as calm as the mirror of a celestial lake, Columbus observed “a wonderful thing, that when he left the Canaries for this Española, having gone 300 leagues to the west, then the needles declined to the northeast one quarter, and the North Star did not rise but 5 degrees, and now in this voyage it has not declined to the north-west until last night, when it declined more than a quarter and a half, and some needles declined a half which are two quarters; and this happened suddenly last night.”2

But only the following day, on Friday 17 August 1498, after crossing more than 37 leagues on a quiet sea, the admiral realized the epochal event that had just happened:

He says that not finding islands now, assures him that land from whence he came is a vast mainland, or where the Earthly Paradise is, ‘because all say that it is at the end of the east, and this is the Earthly Paradise,’ says he.3

Narrated in terms of disconcerting simplicity, the presumed crossing of a region where the earthly paradise hypothetically was thought to be located did not arouse any suspicion or skeptical questions in the mind of the narrator, Father Bartolomé de las Casas, just as it did not stir even the slightest shadow of doubt in the navigator’s mind. In fact, for both of them and for most of their contemporaries, the historical, real, and tangible existence of paradise was an unquestionable fact. The only unresolved issue remained the geographical position of the garden where “youth without old age and life without death” could be found.

Christopher Columbus did not spare any effort to decipher the enigma of the historical paradise, recorded in the book of Genesis. As a proof of his keen interest in finding the terrestrial paradise, we can read the numerous pages dedicated to this subject in his letter dated (around) May 30, 1498, sent to their royal highnesses, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile.4 One might say that all the intellectual authorities of the era are invited to this feast of theories regarding the location of the Garden of Eden. Aristotle, Strabo, Pliny, Ptolemy, Saints Ambrose, Augustine, Bede the Venerable, Isidore of Seville, and many others all attest to his firmly conviction that Columbus had discovered the geographical position of paradise—“whither no one can go but by God’s permission.”5

As we will see below, all the interpretations and theories proposed by this unparalleled adventurer show us that the existence of a geographical location for the terrestrial paradise,—the garden where God placed Adam and Eve—, was still considered, in the fifteenth century of Christianity, a certain historical fact.

Confronted with this certainty, we can wonder what answer should be given to someone who will ask us—straightforwardly—where Paradise is located. Saint John Chrysostom did not hesitate to ask his Christian fellows precisely this question. And I can assure you, in full confidence, that this is really one of those very few questions which deserve an answer from any deserving Christian.

The treasure of Saint Isidore

In his letter to Their Majesties, Ferdinand and Isabelle, Columbus explicitly mentions the name of the intellectual giant of the first Christian millennium who passed on to posterity the literal, historical interpretation of the paradise: Saint Isidore of Seville.

He is the one who, in that phenomenal encyclopedic synthesis called Etimologiae, depicts—in the 14th book—both the location and the nature of paradise in terms that will be used by Saint Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologica. Saint Isidore’s vivid narrative, naïve and yet so picturesque, is worth quoting entirely:

Paradise is located in the east. Its name, translated from Greek into Latin, means ‘garden.’ In Hebrew in turn it is called Eden, which in our language means ‘delights.’ The combination of both names gives us the expression ‘garden of delights,’ for every kind of fruit-tree and non-fruit bearing tree is found in this place, including the tree of life. It does not grow cold or hot there, but the air is always temperate. A spring which bursts forth in the center irrigates the whole grove and it is divided into the headwaters of four rivers. Access to this location was blocked off after the fall of humankind, for it is fenced in on all sides by a flaming sword, that is, encircled by a wall of fire, so that the flames almost reach the sky. Also the Cherubim, that is, a garrison of angels, have been drawn up above the flaming sword to prevent evil spirits from approaching, so that the flames drive off human beings, and angels drive off the wicked angels, in order that access to Paradise may not lie open either to flesh or to spirits that have transgressed.6

In this point of my investigation, before returning to Christopher Columbus’ ideas, it should be useful to summarize the essential points in Saint Isidore’s text. First, after the fall of the ancestors of the human race, Adam and Eve, the access to paradise is restricted by God Himself. Secondly, the forbidden garden is hidden somewhere in the East (that is why the text about it is included, in the book of Isidore, in the section entitled ‘Asia’). Thirdly, the climate is temperate, perfect to facilitate eternal life. Fourthly, people are prevented from entering paradise by a fire wall; any attempt by the fallen angels to return here is rejected by the cherubs.

Columbus’ pear

As for Christopher Columbus, we find in his accounts almost all the details mentioned by Saint Isidore. But before seeing, one more time, how all these are included in the admiral’s descriptions, I must emphasize that the he was deeply convinced that the ‘garden of delights’ really existed somewhere in our fallen world. In other words, for him, Paradise was not a myth but a historical reality.

It is precisely this conviction that makes Columbus articulate a framework in which all the details in Saint Isidore’s depiction can fit. This grandiose composition confirms the formidable finding—dated August 17, 1498—reported by Father Bartolomé de las Casas: “(…) that land from whence he came is a vast mainland, or where the Earthly Paradise is.”

Confident that he had discovered unknown territories which belong to India, Columbus follows the geographical narrative of Saint Isidore, who wrote that Paradise was hidden somewhere in Asia (i.e. in the East).7 In his opinion, the recorded climatic changes—especially the moderate temperatures following days of terrible heat—also indicated the proximity of heaven. Similarly, the presence of abundant waters shows that that the spring of the four rivers mentioned in the Book of Genesis is closer and closer. Corroborated, all these details transform Columbus’ suppositions into an irrefutable conviction:

There are great indications of this being the terrestrial paradise, for its site coincides with the opinion of the holy and wise theologians whom I have mentioned; and more over the other evidences agree with the supposition, for I have never either read or heard of fresh water coming in so large a quantity, in close conjunction with the water of the sea; the idea is also corroborated by the blandness of the temperature; and if the water of which I speak, does not proceed from the earthly paradise, it appears to be still more marvelous, for I do not believe that there is any river in the world so large or so deep.8

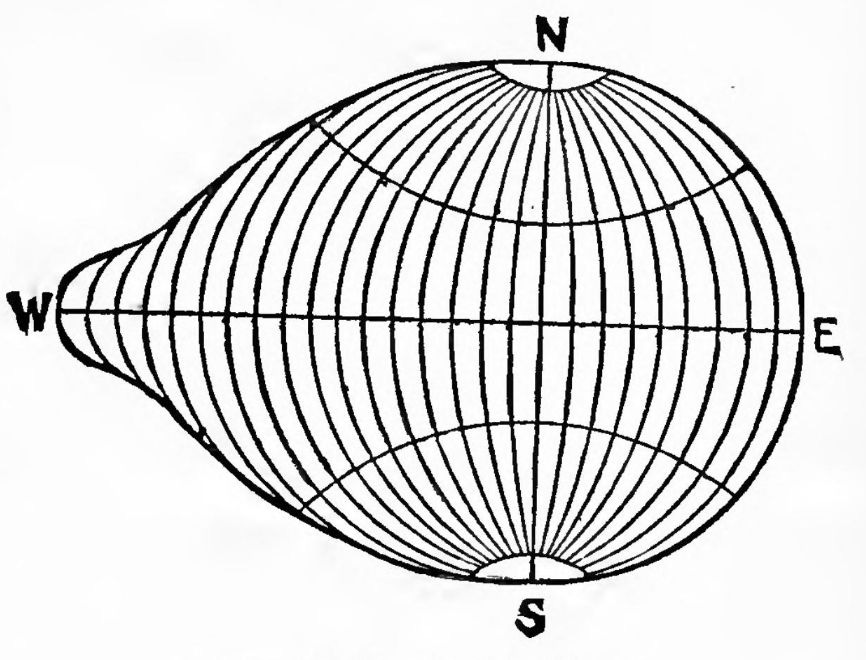

Despite the similarities between the description proposed by the author of the Etimologiae and that of Christopher Columbus, there is a significant element which is missing: the protective fire wall which surrounds the paradise mentioned by the learned Spanish bishop. This being the case, we can legitimately wonder what is the protection of the entrance into the garden from which Adam and Eve were exiled? Columbus’ answer is as simple as possible: altitude. In other words, the height on which it is located renders impossible the access of any person or boat. This is because the Paradise, in the view of the Genoese navigator, is on the top of a mountain. This mountain, which soars in the sky, is not peaked, but flat, whose shape is that of a pear:

I do not suppose that the earthly paradise is in the form of a rugged mountain, as the description of it have made it appear, but that it is on the summit of the spot, which I have described as being in the form of the stalk of a pear; the approach to it from a distance must be by a constant and gradual ascent; but I believe that, as I have already said, no one could ever reach the top.9

As we can see in many studies dedicated to Christopher Columbus’ voyages, the shape of the world he proposed often led to ironic remarks. So far, however, I have not found any satisfactory explanation of the logic that led to such a vision. In my opinion, what is significant is the fact that this logic derives directly from the author’s belief that paradise exists somewhere in our fallen world. But what does this have to do with the shape of the world?

Precisely in this point comes the unexpected answer: only in this way the survival of the original homeland of mankind after the biblical flood can be explained. In the absence of this mountain, the flood’s waters would sink forever the garden that shelters the Tree of life described both in the Book of Genesis and in the Revelation of Saint John. That is why Columbus’ world must have such a strange form. Not of an egg, but of a pear.

Olson, Julius E. and Edward G. Bourne (editors), The Northmen, Columbus and Cabot, 985-1503, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1906, p. 363. From here on, this work will be quoted as The Northmen…

The Northmen…, p. 363. In the Spanish edition from 1875 the original text can be read at the same page quoted above:

Dice aquí una cosa maravillosa, que cuando partia de Canaria para esta Española, pasando 300 leguas al Oueste, luego nordesteaban las agujas una cuarta, y la estrella del Norte no se alzaba sino 5°, y agora en este viaje nunca le ha nordesteado, hasta anoche, que nordesteaba más de una cuarta y media, y algunas agujas nordesteaban medio viento, que son dos cuartas; y esto fué, todo de golpe, anoche.

The Northmen…, pp. 364-365. Historia de las Indias, p. 315:

Dice, que con no hallar ya islas se certifica, que aquella tierra de donde viene sea gran tierra firme, ó á donde está el Paraíso terrenal.

Translation by R. H. Major: Select Letters of Cristopher Columbus, with Original Documents, relating to his Four Voyages to the New World, London, 1847, p. 135 sq. Since now on, this edition will be quoted as Select Letters of Cristopher Columbus…

Select Letters of Cristopher Columbus…, p. 137.

Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach și Oliver Berghof (with the collaboration of Muriel Hall), The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 285-286. Here is the original text as it can be read in S. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi, Opera Omnia, Tomus IV, Etymologiarum, Libri X. posteriores, Romae, 1850, pp. 143-144:

Paradisus est locus in orientis partibus constitutus, cuius vocabulum ex Graeco in Latinum vertitur hortus: porro Hebraice Eden dicitur, quod in nostra lingua deliciae interpretatur. Quod utrumque iunctum facit hortum deliciarum; est enim omni genere ligni et pomiferarum arborum consitus, habens etiam et lignum vitae: non ibi frigus, non aestus, sed perpetua aeris temperies. E cuius medio fons prorumpens totum nemus inrigat, dividiturque in quattuor nascentia flumina. Cuius loci post peccatum hominis aditus interclusus est; septus est enim undique romphea flammea, id est muro igneo accinctus, ita ut eius cum caelo pene iungat incendium. Cherubin quoque, id est angelorum praesidium, arcendis spiritibus malis super rompheae flagrantiam ordinatum est, ut homines flammae, angelos vero malos angeli submoveant, ne cui carni vel spiritui transgressionis aditus Paradisi pateat.

Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and Oliver Berghof (with the collaboration of Muriel Hall), The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 285-286.

Select Letters of Cristopher Columbus…, pp. 137-138.

Select Letters of Cristopher Columbus…, pp. 137.

I have read Blessed Catherine Emmerich's visions, collected by Clemens Brentano. She said that Adam and Eve were only in the Garden one day, and that she has "seen Paradise far, far off like a strip of land directly under the point of sunrise. When the sun rises, it mounts up from the right of that strip of land which lies east of the Prophet Mountain and just where the sun rises. It looks to me like an egg hanging over indescribably clear water which separates it from the earth. The Prophet Mountain is, as it were, a promontory rising up through that water. On that mountain, one sees extraordinarily verdant regions broken here and there by deep abysses and ravines full of water. I have, indeed, seen people climbing up the Prophet Mountain, but they did not go far." Her description of the Prophet Mountain is rather intriguing and mystical. Who knows? I would not be surprised if it does exist in some form in our world, since from it came our first people, in the flesh.