Sacred Symbols and the Destruction of the Holy Mass

Introduction to the Mystagogic Theology of the Catholic Church

Many Questions, Only One Answer

What is the difference between a medieval Gothic Catholic church built according to the canons of sacred architecture—Notre Dame de Paris—and a modern (i.e. modernist) church like the Cathedral of Our Lady in Los Angeles? Here is the answer: the first one is a sacred symbol, just like almost every object contained within it. The second one, despite being (probably) consecrated according to the rituals in use and containing certain paintings with Christian content, is an unholy, profane building.

Consecrating such an architectural monstrosity was as if someone had sprinkled holy water on the structure of a nuclear missile base. If such a thing were done (and we certainly know that terrible things have been done, like the “blessing” of Stalin’s statue or of a night club), no one would ever dare to say that the power plant’s architecture had become a sacred place. Only when the principles of Catholic sacred art are respected does the architecture, furniture, statues, images, and other religious objects become true religious symbols.1

What is the difference between the manner in which a priest serves in the context of the “ordinary” reformed liturgy of Pope Paul VI and a priest who serves the Roman Catholic liturgy, of apostolic origin, known as the “Gregorian Liturgy” or the “Mass of the Roman Rite”? In the latter, every gesture of the priest, every detail of the ritual, every liturgical element is a symbol.2 And it’s not only the priest, but also us, the simple lay Christians, who use symbolic gestures. The sign of the holy cross made when we pray at home or pass by a Catholic church, or when we feel threatened by temptation, is such a symbolic gesture.

Let’s recapitulate. The architecture of the church, the religious gestures of the priests and the faithful, the words of prayers, the Gregorian or Byzantine sacred music, the liturgical vestments, and so on—everything in the context of an authentic Christian church that respects sacred traditions—is a symbol. The inspired texts of the Holy Scriptures—whose author is God Himself—also contain a vast multitude of symbols upon which both the prophets and the faithful Jews, as well as the Fathers and Doctors of the Christian Church, followed by believers from all eras, have meditated for thousands of years. Saint Dionysius the Areopagite unveiled in his works the principles that allow us to authentically interpret the biblical symbols. Similarly, each type of sacred art is subject to analogous principles of interpretation.

Nothing Sacred

Unfortunately, in the past decades, the notion of ‘symbol’ and its exceptional value have been completely forgotten or ignored. The secularization of the modern world and the desacralization of Christianity have created a context that is non- or even anti-religious. For example, the cathedral in Los Angeles is not—according to the criteria of sacred architecture—a Christian church. This is because it does not adhere to the principles that guided the creators of architectural marvels like Sainte-Chapelle or Notre-Dame de Paris. The same assertion can be made about many religious artistic creations that, despite their appearances, are not sacred. Why is this so? Precisely because they were not conceived and created to be symbols. In fact, marked by the obsession with ‘freedom,’ the modern mentality is completely allergic to any type of canon, to any type of rule, to any form of authority.

As we have seen in the case of the sacrilegious manner in which the Holy Eucharist was treated during the previous World Youth Day event (Portugal, 2023), we realize that in the Novus Ordo context almost no one is preoccupied by such a significant deficiency. This is because, lacking the necessary mystagogical formation and the right theological and philosophical frame, none of those in positions of authority recognize the true significance and value of sacred art and religious symbols. We can cite countless anomalies and sacrileges: (non)Catholic churches that resemble sports halls (when they don’t look like flying saucers or prison buildings); altars that seem like tables designed in dubious styles; liturgical vestments painted/adorned with profane and secular signs; priests who behave like the animators of clubs or dance arenas etc. And yet, even when they are outright sacrilegious, no one seems to attach any importance to them. The general attitude of most hierarchs is as shocking as that of Pope Paul VI who, when asked by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre if he was aware that in France, at least twenty-three different Eucharistic prayers were being chaotically used, responded curtly:

“Many more, Monseigneur, many more!”3

I don’t know whether the Pontiff’s response is evidence of cynicism or simply helplessness.

Symbols and Icons: Windows to the Kingdom of Heaven

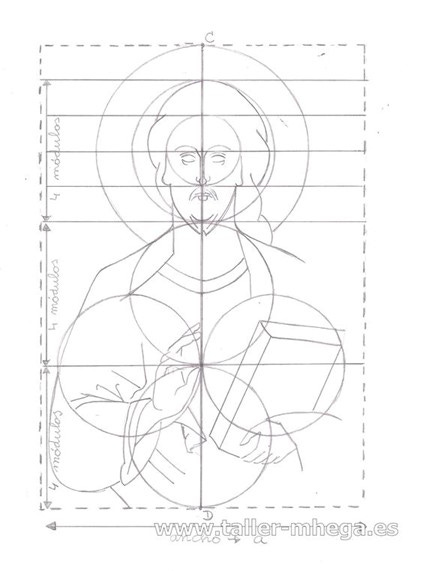

In order to better understand what makes a work of art an authentic symbol, we will use an extraordinarily relevant example extracted from a recent article written by Miss Hilary White.4 Highlighting the significant deviations from the traditional Byzantine icon canons in the kitsch paintings and mosaics of Marko Ivan Rupnik, she provided us with the—truly illuminating—example of the invisible lines that define the context of the artist’s creativity:

Looking at such a rigorous, precise and harmonious organization, we immediately grasp the insurmountable chasm between the canon of Byzantine Christian painting, faithfully upheld by all traditional iconographers, and the chaotic, kitsch creations of modernists. In the case of Byzantine icons, we are dealing with ‘windows’ open to the unseen world—the eternal place where the supernatural depicted beings reside—, thus representing true sacred symbols. However, in the case of paintings by ego-centric and ego-maniacal artists who disregard any canon and only follow their own passions and phantasms, we are not dealing with sacred art. This holds true even when, as is the case with the Baroque paintings of the Renaissance, we encounter exceptionally talented authors. The pure aesthetic beauty of a painting or a church is insufficient to transform a work of art into a symbol. The canon—that is, the entire richness of the structural lines (and hidden numbers) defining the background of the icon presented by Miss White—is what transforms a beautiful work into an authentic religious symbol.

Heaven on Earth: the Symbolic Universe

Visiting the sacred edifices of Catholic churches, such as Notre Dame de Paris, we realize that one of the fundamental dimensions of the Christian Tradition is the overwhelming richness of the multitude of symbols that we are invited to contemplate. It’s as if we hear the invitation that God addressed to Adam:

Of every tree of paradise thou shalt eat… (Genesis 2: 16).

Not by chance, Father Claude Barthe chose as the subtitle for his book La Messe (The Mass) a highly significant verse from Charles Baudelaire’s poem entitled Correspondences. Through a fortunate inspiration, the English edition bears the very same subtitle: A Forest of Symbols.5 Not only the Liturgy—a synthesis of religious worship—but absolutely all the sacraments operate with symbols. Realizing this, we can say that in the Church, all Christians are invited to live in a symbolic universe. Just as Adam and Eve were invited in the pre-lapsarian beginnings of history to eat from every tree in Eden except for the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, after His first coming to Earth, God invites us in His Church—the Paradise on Earth—to nourish our minds with the meanings of these symbols meant to elevate us toward the Creator of all that exists.

From a complementary perspective, we understand that we are dealing with a symbolic universe that reminds us not only of a forest but also of a cathedral. It’s the beautifully ordered world as God created it before the Fall with Paradise in its center—a world that He invites us to contemplate now, after the fall, in the church, discovering the divine reasons behind all the symbols and the whole universe they constitute together.

In This point I must emphasize the gravity of eliminating any detail from this well-articulated universe. Just as each element carries its own significance, the ensemble itself holds a complete symbolic value. In the same way that the Roman Catechism states that none of the ceremonies accompanying the essential part of the sacraments “cannot be omitted without sin,”6 similarly, no symbol can be removed from the Church without impoverishing and finally destroying the contemplative life to which all believers are invited. From this perspective, any pseudo-reform meant to change or eliminate a symbol—as well as the replacement of the Mass of the Roman Rite—is what our Lord Jesus Christ described as “the shutting of the kingdom of heaven against men” (Matthew 23: 13).

Unfortunately, the widespread abandonment of mystagogical initiation, have deepened the ignorance of Christians, turning them into illiterates of the mystical language of sacred symbols.

Symbols and Reality

Nowadays, to say that something is ‘symbolic’ sounds similar to when we say that, by convention, the red color of a traffic light symbolizes stop, while green symbolizes proceed. Such a choice of colors is entirely arbitrary. We can use—instead of red and green— any other colors we like: blue for stop and purple for proceed. Unlike these human conventions, sacred symbolism is not arbitrary. The Roman Catechism categorically states this, affirming that the sacraments “are signs instituted not by man but by God.”7

If in the realm of philology, we learn about the “arbitrary nature of linguistic signs” (Ferdinand de Saussure). This ‘arbitrariness’ is a phenomenon that occurred after Babel, and it has nothing to do with sacred symbols. Such a serious confusion simply destroys the notion of sign/symbol—because it would transform it into something conventional, unreal, thus ultimately untruthful. On the contrary, the religious symbols/signs in the Liturgy and Christian Sacraments—through the ontological participation on eternal archetypes—are the only things fully real, in comparison to everything contained in this fallen world, dominated by death and destined for final destruction by fire (II Peter 3, verses 7 and 12). Concretely, the consecrated Holy Altar placed inside in a church is absolutely real in comparison to the eroding stone from which it has been made. Why is so? Because the Holy Altar is in a mysterious relationship with its archetype that is God—the Rock—Himself, while the perishable stone is related only to the substantial form (in the Aristotelian-Thomistic language) of the ‘stone.’ Similarly, any sacred symbol is incomparable much more real than any common thing/creature from earth.

After succumbing to the temptation of the Devil ( = διάβολος—a Greek word that has a meaning that is the opposite of the σῠ́μβολον), original sin separated the first humans—Adam and Eve—from God, along with the entire world. Since then, everything is subject to death. The sacraments and the symbols, established by God Himself through the means of His Revelation contained in Holy Scripture and the Church, are the instruments through which we receive the graces lost by Adam and Eve in Paradise. In essence, before the incarnation of the Savior Christ, the world was like the basket of a balloon whose strings had been cut: thus, in free fall. After the incarnation, God, through the unceasing graces transmitted to us through the Holy Sacraments and all sacred symbols, reattaches the basket to His eternal world. And this is done with the golden cords (Lat. catenae aureae) of His Glory, Glory which He Himself bestows upon us when we offer Him our perishable, fleeting glory as a sacrifice.

What is a Symbol

If the term ‘symbol’ (Gr. σύμβολον) comes from the ancient Greek culture, in the Latin culture, the term that prevailed due to the enormous influence of St. Augustine is ‘sign’ (Lat. signum). These interchangeable notions are inseparably linked to that of ‘sacrament.’ The Roman Catechism makes this crystal clear:

Whoever peruses the works of Saints Jerome and Augustine will at once perceive that ancient ecclesiastical writers made use of the word sacrament, and sometimes also of the word symbol, or mystical sign or sacred sign, to designate that of which we here speak.8

One of the most well-known definitions of our concept was proposed by Saint Augustine in De Civitate Dei:

Sacramentum est sacrae rei signum (X, 5) – The sacrament is a sign (= symbol) of a sacred thing.9

We instantly notice the three key elements: the sacrament (for example, Holy Baptism), the sign/symbol (in the case of Baptism, water), the sacred thing (the sanctifying grace that is given to us through the sacrament). First, the Latin term sacramentum indicates what this is about: a medium for transmitting a holy thing (i.e., divine grace). The Greek word is equally significant: μυστήριον (i.e., ‘mystery,’ ‘secret rite’). The sacrament conveys to us in a hidden, unseen manner the sanctifying grace that God bestows upon all who receive it. Then, the definition tells us that it is a symbol/sign of a sacred thing. For example, after the exorcism and blessing, the water of Baptism is not just any water: it somehow becomes the very water from the beginnings of creation over which the Holy Spirit hovered (Genesis 1:2).

As we know from the conversation between the Savior Christ and Nicodemus (John chapter 3), every Christian is reborn, thus able to see the Kingdom of God. Re-birth literally means re-creation: each one of us has been entirely remade through God’s power through Holy Baptism. A remaking that, though incomplete (for our bodies are still mortal), gives us the possibility to enter directly into the Kingdom of God—if we die in a state of sanctifying grace. However, all these things are mysterious, hidden, being symbolized by the baptismal symbol, which is purified and blessed water. Yet, everything happens for the purpose of sanctifying us:

You shall be holy, for I am holy. (1 Peter 1:16)

Another similar definition has been proposed by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux:

A Sacrament is a visible sign of an invisible grace, instituted for our justification.

Through the correct performance of consecration and blessing rituals, profane elements from our world (salt, water, oil, church objects, the altar stone, etc.) are truly transformed into religious objects that are in a mysterious and powerful connection with the unseen, eternal world. Just as paradoxically, through baptism, the Christian is both on earth and in heaven. These sacred objects—symbols/signs—serve as windows to that heavenly world where God is glorified by angels and saints. The eyes through which we can contemplate the wonders of heavenly Jerusalem are the faculties of our mind, purified through humility, illuminated by baptismal grace, and formed through mystagogical catechesis.

To get a better understanding of the principles of Christian sacred architecture I warmly recommend the excellent documentary Building the Great Cathedrals: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/building-the-great-cathedrals/ [Accessed: 15 November 2024] and Jean Hani’s book, The Symbolism of the Christian Temple (Angelico Press, 2016).

An well-formed Catholic does not say that the Holy Eucharist—the true and real body and true and real blood of the Savior—is a symbol. In this way, he emphasizes the doctrine of the Real Presence of our Lord, Jesus Christ, in it. All these matters will be explained at the appropriate time.

Here is a presentation of the 1976 audience: https://sspxasia.com/Documents/Archbishop-Lefebvre/Apologia/Vol_one/Chapter_14.htm [Accessed: 15 November 2024].

Hilary White, “Who is Marko Ivan Rupnik, & why did the Bergoglians shelter him?:” https://remnantnewspaper.com/web/index.php/articles/item/6733-who-is-marko-ivan-rupnik-why-did-the-bergoglians-shelter-him [Accessed: 15 November 2024].

The complete original French title is La Messe. Une forêt de Symboles (Via Romana, 2011). The full title of the English edition is A Forest of Symbols: The Traditional Mass and Its Meaning (Angelico Press, 2023).

Catechism of the Council of Trent for Parish Priests Issued by Order of Pope Pius V, Translated by John A. McHugh O.P. and Charles J. Callan O.P., New York, 1934, p. 152.

Op. cit., p. 146.

Op. cit., p. 142.

The complete text is as follows: “Sacrificium ergo visibile invisibilis sacrificii sacramentum id est sacrum signum est”—“A sacrifice, therefore, is the visible sacrament or sacred sign of an invisible sacrifice.”

I think I must attend one of the worst 1969 creations of a "church." It is round and looks, on the outside, to be an ugly dark brown wooden BARN (I've seen beautiful barns, but not this one). The only hint that it is a "church" from the outside is a stark white plain cross erected among some plants. It is hideous- and the inside is not much better. It must have been brutalist-inspired and people have tried to soften it over the years by adding wood paneling and such. It's is a terrible trial, but I have no other choice at the moment... the appearance of a structure for praying really does affect one's attempts at rightful worship. Thank you for reiterating that!

Are there "canons" of sacred architecture? I know there are canons of iconography.