Why do we Need Literature? An Answer Inspired by Saint Thomas Aquinas

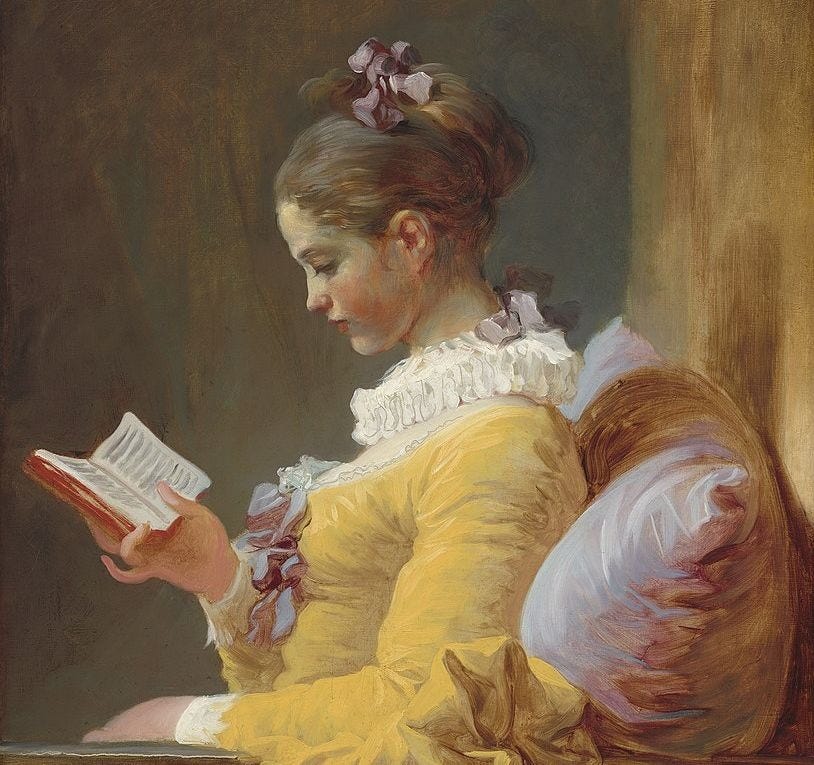

The Joy of Reading in Turbulent Times

Like any other artistic creation, a literary work—whether it be a novel, a short story, or an epic poem—can demand hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of work. What truly intrigues an outside observer is the absence of a concrete gratification associated with a laborious ‘job’ as that of a fiction writer. Consequently, many may assume that the purpose of such an ‘unproductive’ work is to satisfy the vanity of the writers themselves or, eventually, to serve the aspirations of those who hope to become rich as a result of the fame they attain through their literary creations. Without considering that those writers driven by such goals are necessarily mediocre, I will leave them aside. In addressing our issue, we must take into consideration those creators who, like Miguel de Cervantes, Alessandro Manzoni, Gilbert Keith Chesterton or Joseph Conrad, consider writing a moral duty arising from the talent that God gave to them. So, why is their work valuable? Why do we need fiction literature?

Without wasting your time, I can provide an immediate response: because we need joy. My answer implies that one of the most concerning phenomena we all face in these times is the absence—or loss—of joy. I mean true, Christian joy. Even though we often hear someone say something like “It’s fun!”, very few find true joy. Indeed, I am absolutely certain that a substantial number of people will readily acknowledge that in our fallen world, finding a true joy is increasingly challenging. And how could it be otherwise in such turbulent times, constantly threatened by various ‘viruses’? In this tense situation, the topic of ‘stress’ has become ubiquitous. Often, the usage of this term is merely another way of describing the same underlying truth: our souls are growing weary. It is a given fact that in addition to the challenges of contemporary (post)modern life, the weariness of the soul is a common experience which, it is true, has been known in all eras of history.

That is why we need rest. Rest for our souls. It is that kind of rest Frodo discovered in Rivendell after he was almost killed by the dark Nazgûls. This particular form of rest is designated by the ancient Greek word eutrapelia (εὐτραπελία), which originally denoted the ability to have a fruitful and pleasant conversation. It signifies not rest for an exhausted body, but rather rest for a fatigued, weary soul.

If you’re curious who is the author who inspired me such a response, the answer might come as a surprise: Saint Thomas Aquinas. In his immortal masterpiece, Summa Theologica (II-II, Q. 168, art. 2), he reflects on a very interesting question that may not have an immediate link to literature: “Whether there can be a virtue about games?”

The explanation given by the Angelic Doctor is more than remarkable. It is truly wise:

Just as man needs bodily rest for the body’s refreshment, because he cannot always be at work, since his power is finite and equal to a certain fixed amount of labor, so too is it with his soul, whose power is also finite and equal to a fixed amount of work. Consequently when he goes beyond his measure in a certain work, he is oppressed and becomes weary, and all the more since when the soul works, the body is at work likewise, in so far as the intellective soul employs forces that operate through bodily organs. Now sensible goods are connatural to man, and therefore, when the soul arises above sensibles, through being intent on the operations of reason, there results in consequence a certain weariness of soul, whether the operations with which it is occupied be those of the practical or of the speculative reason. Yet this weariness is greater if the soul be occupied with the work of contemplation, since thereby it is raised higher above sensible things; although perhaps certain outward works of the practical reason entail a greater bodily labor. On either case, however, one man is more soul-wearied than another, according as he is more intensely occupied with works of reason. Now just as weariness of the body is dispelled by resting the body, so weariness of the soul must needs be remedied by resting the soul: and the soul’s rest is pleasure.

(…)

Now such like words or deeds wherein nothing further is sought than the soul’s delight, are called playful or humorous. Hence it is necessary at times to make use of them, in order to give rest, as it were, to the soul. This is in agreement with the statement of the Philosopher (Ethic. IV, 8) that “in the intercourse of this life there is a kind of rest that is associated with games:” and consequently it is sometimes necessary to make use of such things.1

As we can see, our Common Doctor takes into account both dimensions of the human person, which are limited and profoundly affected by the current post-lapsarian state: the body, with its need for physical rest, and the soul, with its specific spiritual need for rest. This rest for the soul presupposes a certain form of “inner pleasure”—or joy. The notion of eutrapelia is the one that indicates this type of pleasure/joy of the soul and seeks to distinguish legitimate ways of attaining joy from those that can endanger our salvation. And, as you would expect, the greatest issue relates to the lack of modesty and the indecency which, in the ancient pagan world as well as in today’s world, were widespread.

Consequently, no pleasure should be sought “in indecent or injurious deeds or words.” For us, who live in the post-sexual revolution era that began in the 60s and 70s, this statement may seem rather obvious. However, the careful observation of the principle of purity of heart, both in ourselves and in our children, remains crucial.

Another significant issue is the balance of the mind. As Saint Ambrose of Milan emphasized, it is essential that while seeking relaxation, the mind does not lose its focus on matters of importance and the deeds necessary for the salvation of the soul. We must always bear in mind the golden rule of prioritizing the kingdom of God and its perennial values, as stated in Matthew 6:33:

Seek ye therefore first the kingdom of God, and his justice, and all these things shall be added unto you.

Last but not least, we must exercise caution, just as we do in all other human actions, by aligning ourselves with the appropriate individuals, timing, and environment, while considering other relevant circumstances. In essence, we ought to engage in the right activities at the right time and in the right context. This principle applies not only to significant professional or religious activities but also to relaxing activities such as reading, watching, listening, or playing.

But wait! St. Thomas speaks about games. Can literature be included in this category of activities for the rest of the soul? To the extent that fictional literature represents a form of ‘play’ for both the author and the readers, certainly, yes. However, it is not merely that. Just as it is often acknowledged in the case of certain games, literature also contains other significant pedagogical and educational dimensions. The way characters in novels speak, behave, act, and react in certain situations—all of these reflect values that can be positive and worthy to be imitated, or negative and to be avoided. Similar to dramatic art or cinema, literature creates and presents ‘heroes’ or ‘anti-heroes’ to the audience.

This is why, as warned by Saints such as Basil the Great, Teresa of Ávila, or Alphonsus Maria de Liguori, parents have a sacred duty to carefully choose the readings for their children. While the criterion of intrinsic beauty of a novel or a poem should always hold a prominent place, the observation of a virtuous life must also be another fundamental criterion—as recommended by St. Basil the Great in his famous Address to Young Men on How They Might Derive Benefit from Greek Literature regarding ancient poetry:

To begin with the poets, since their writings are of all degrees of excellence, you should not study all of their poems without omitting a single word. When they recount the words and deeds of good men, you should both love and imitate them, earnestly emulating such conduct. But when they portray base conduct, you must flee from them and stop up your ears, as Odysseus is said to have fled past the song of the sirens, for familiarity with evil writings paves the way for evil deeds.2

The virtuous life has always been the main goal of any true Christian. This is the primary reason for assessing the quality of reading proposed by Saint Basil the Great. Without excluding the demand for an heroic life, grounded in the perennial values of the Ten Commandments, the joy of reading a good novel or a remarkable poem remains an ever-present aspect of life that can provide the much-needed rest for our souls navigating the turbulent sea of a twilight world.3

Here is the text: https://www.newadvent.org/summa/3168.htm#article2 [Accessed: 30 August 2024].

The entire text can be read online here: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/pearse/morefathers/files/basil_litterature01.htm [Accessed: 30 August 2024].

Literature, Truth and Beauty

In an interview that I had the honor and joy of conducting almost 20 years ago, in 2005, Joseph Pearce revealed that his vocation is to mediate the encounter of as many readers as possible with Beauty. And not just any kind of beauty, but one revealed by reading the works of literary giants like W. Sh…

I do so agree - reading a good novel can sometimes open the mind to new ways of thinking that be very helpful. Thx for the reminder!

Long but very comprehensive thanks John!