I owe my discovery of Joseph Conrad’s novels to Thomas Mann. A sentence from The Story of a Novel. The Genesis of Doctor Faustus made me dive into the turbulent waves of the online network, navigating to antiquarian bookstores from where I purchased all the fiction mentioned by the German author:

As far as reading was concerned, the novels of Conrad still seemed the most appropriate to the present stage of my own novel-or, at any rate, the entertainment that least disturbed it. I read The Nigger of the Narcissus, Nostromo, The Arrow of Gold, An Outcast of the Islands, and the rest of those excellent books, read them with great pleasure.1

Motivated by such strong recommendations (“manly, adventure-loving, linguistically superior, and psychologically and morally profound narrative art”2), I embarked on a fascinating literary journey, a journey that continues to this day. I have always paid special attention to those books I consistently return to. Re-reading is the best barometer for detecting authors who matter. Typically, they fall into two classes: those I re-read to savor the beauty of their words, and those I re-read to learn, delve deeper, and understand. Joseph Conrad belongs to both categories.

I marvel at the discreet sparks of black agate scattered across most of its pages, tracing his literary craftsmanship in a perpetual course of creative writing. Thomas Mann’s recommendation, whose well-tempered enthusiasm is worth more than a thousand words, is not accidental. The revelation brought about by the author of Doctor Faustus is due to the unparalleled craftsmanship that found its full realization in the memorable characters of both authors.

In Joseph Conrad, as in Thomas Mann, the spectacle of the world is completely absorbed into the vast subjective geography of the protagonists. Their universe can only be geocentric, a geocentrism whose axis is composed of the sum of fictional subjects. Their paths of maturation, described with microscopic precision, encapsulate, for those who have the patience to re-read and the eyes to see, the traces of the titanic work of the two in the marble quarries where they carved their characters. Their stature compels me to limit myself to speaking only about the Polish author.

If you detect the signs of an elective affinity, you will not be mistaken. The words of little Konrad on the back of a photograph intended for his grandmother have sealed my aesthetic preferences:

To my dear grandmother who helped me to send cake to my poor father in prison–Pole, Catholic, gentleman, July 6, 1863.3

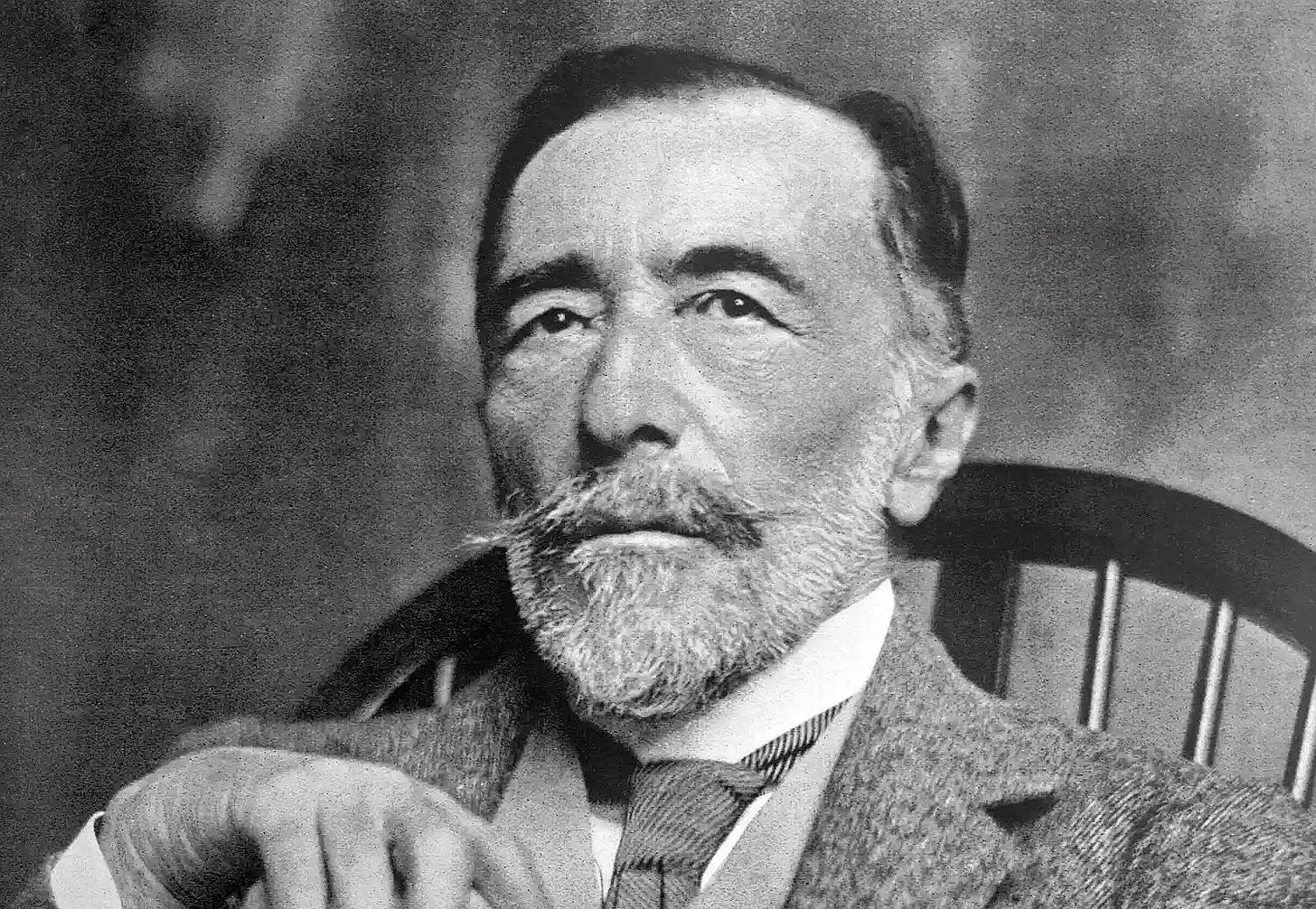

As already demonstrated by exegetes like Mikołaj Gliński, these three attributes–Polish, Catholic, and gentleman–circumscribe the essence of the personality of Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski (1857–1924). One of the most significant experts on his works, Zdzisław Najder, is quoted by Gliński to underscore the ethical core of his prose based on ideas such as “honour, fidelity, and duty as essential moral values.”4 Well-assimilated into Polish culture, these ideas of clear chivalric inspiration are found in the works of writers who embody the values of classical European aristocracy, including Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Alessandro Manzoni, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, and Kazuo Ishiguro (just to name a few).

If, for Medieval and Renaissance authors, the gentleman (i.e., the noble) was the ‘measure’ of all things, the moderns are prisoners of the tragic condition of a world where proletarianization and class amalgamation took place under the mask of the ‘tramway democracy’ denounced by the Romanian writer Nicolae Steinhardt. Of course, Edmund Burke is the one who described the condition of true aristocrats crushed by the ‘democratic’ fervor incited against unpopular minorities:

The age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever. Never, never more, shall we behold that generous loyalty to rank and sex, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart, which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom! The unbought grace of life, the cheap defence of nations, the nurse of manly sentiment and heroic enterprise, is gone! It is gone, that sensibility of principle, that chastity of honor, which felt a stain like a wound, which inspired courage whilst it mitigated ferocity, which ennobled whatever it touched, and under which vice itself lost half its evil by losing all its grossness!5

How to survive in the age of cynicism and vulgarity turned into a way of life? How to be a gentleman and, if necessary, a hero, amidst those for whom the title ‘Count,’ given to Conrad, was merely a malicious nickname? Transplanted for a few years to Marseille, between 1874 and 1878, Korzeniowski quickly discovered that the answers to these questions were hard to find. Evidence of this is his, fortunately unsuccessful, suicide attempt. Starting in 1895, the year of his debut with the novel that fascinated Mircea Eliade, Almayer’s Folly, fiction literature will serve as his workshop for creating and testing that human model whose archetype is found in the delicate fabric of all his characters: the plausible hero.

Used by the Romanian writer and literary critic Mircea Mihăieș in his captivating monograph The Metaphysics of Detective Marlowe, the notion of plausibility aspires to “a deeper realism than that based on the so-called mimesis of realists.”6 Its value lies in the fact that Raymond Chandler, the author of the famous hard-boiled stories featuring the detective Philip Marlowe, sharply criticized the ‘falsification’ of characters. This critique underscores the unwavering commitment to authenticity and real life, a dedication not merely asserted but substantiated through the creation of incredibly credible characters. Here is the evidence that even critics of Harold Bloom’s caliber, who dismiss the genre of detective literature due to the simplicity of clichéd characters, can be mistaken.

Perhaps those readers that are more demanding will react to the proximity between a classic of English literature and an author of minor detective stories. I hasten to assure them that I have serious reasons for such digressions. And I am not alone in the library! Peter Rozovsky, a diligent popularizer of detective literature, described the astonishment with which he discovered that the narrator of Conrad’s extraordinary novel Lord Jim is named... Marlow.7 Furthermore, the stylistic descriptions of the characters strikingly resemble the writings that feature detective Marlowe as the protagonist. However, as I do not want to venture into the labyrinth of a literary history study, I hope that this will suffice.

Those authors in whose hearts a metaphysician resides pay always a special attention to the art of character. This has a very simple explanation. Metaphysicians, in one way or another, yearn to become heroes. Not heroes of fiction or celluloid, but rather heroes of diamond, capable of facing a twilight world that rolls steadily towards the abyss. For what else can one be if they wish to fly with wings of wax?

Once the ideal is formulated, giants with arms as long as the blades of a Quixote windmill come rushing in. Both Conrad and Chandler felt this on their own skin. If something truly seems difficult in the modern world, frustrated not only by formal pronouns, it is the simple fact of trying to be, to behave like a gentleman. The plausible description of such a forbidden being has been the essential mission of Joseph Conrad. The account of the genesis of the novel Nostromo fully reveals such a crucial intent:

As a matter of fact in 1875 or ’6, when very young, in the West Indies or rather in the Gulf of Mexico, for my contacts with land were very short, few, and fleeting, I heard the story of some man who was supposed to have stolen single-handed a whole lighter-full of silver, somewhere on the Tierra Firme seaboard during the troubles of a revolution. On the face of it this was something of a feat. But I heard no details, and having no particular interest in crime qua crime I was not likely to keep that on in my mind.

As we expected, Conrad is not interested in sensationalism. Crimes, no matter how spectacular, hold no interest for him. He reiterates this in the same tone when he emphasizes that “to invent a circumstantial account of the robbery did not appeal to me.”8 The lightning was to strike when it was revealed to him, suddenly and accidentally, “that the purloiner of the treasure need not necessarily be a confirmed rogue, that he could be even a man of character, an actor and possibly a victim in the changing scenes of a revolution.”9 Well, this is an entirely different matter.

The favorite theme of Joseph Conrad is the destiny of a person of character caught in the turmoil of a disordered world. His literary symphonies are nothing more than variations on the heroism of plausible gentlemen. The palette of moral journeys is complete. From the failed Dutchman Almayer, through the Italian Giovanni Battista Fidanza (i.e., “Nostromo”) to the French corsair Peyrol, the absolute value of honor takes precedence for all of them. Even when they renounce, like the prodigal son, their own substance, they are not illuminated by the black sun of the apostle Judas but by that twilight and penitent one of the first pope in history, Saint Peter.

The white gloves that Conrad always wore as a maritime officer are extended and applied to the entire attire of the nearly perfect character, Lord Jim: “He was spotlessly neat, appareled in immaculate white from shoes to hat.”10 Such a pontifical appearance can only be that of a wandering god.

Followed by Captain Charles Marlowe throughout his tumultuous tribulations, the second mate Jim will be dishonored as a result of the most reprehensible act of a maritime officer: the abandonment of his own ship. To atone, he withdraws, aided by the exotic butterfly collector Stein, to the edge of the world, in Patusan. Even in the midst of the jungles of Borneo, Jim remains the same metaphysic gentleman of the Sorrowful Countenance, unwavering in his ethical choices. The chance of rehabilitation seems to smile upon him. But against all signs of a happy future, his best friend, Dain, the son of an influential local leader, is killed due to a strategic error. Drained of thoughts and feelings, Jim stands before the father of the deceased, Doramin, who, overwhelmed, kills him, thus granting him the chance of an honorable resurrection.

Not only in Jim’s case but in the case of most of Conrad’s protagonists, if we trace the proportions of the sublime and the white mixed with the too human, too darkly human, we discover that the characterological alchemy practiced by the British Pole is infinitesimal. Shades of gray abound. The measures of their flawed traits are dosed in such a way that the ordinary reader may believe that he is dealing with that species of abyssal wrongdoers which, in fact, never interested Conrad. Captain Peyrol, from his last autumnal novel, The Rover (1923), is a good example of the dosage of decadent humanity mixed with the grandeur of Olympian heroism.

For at least the first hundred pages, you might think you’re dealing with a pirate retired due to his own biological limits. As you progress, it becomes clear that Peyrol is not only a discreet and fierce adversary of criminal spirit and letter of the French Revolution, but a true fighter who could erupt at any moment. It chills you how peacefully he recalls the mornings when he washed the blood spilled on the deck after hand-to-hand combat with the Malay pirates. While reading, you are convinced that you’re dealing with a pirate steeped in wickedness. Only in the end is such a superficial understanding completely overturned. Through cunning schemes reminiscent of Odysseus, without shedding a drop of blood, Peyrol diverts the British navy from a possible invasion. After you’ve read the last page, it’s hard to claim that you’ve dealt with a hero. If you attempt to understand, however, you will find that plausibility is the only epithet you can safely apply to him.

Relying on first-hand knowledge of the habits and stylistics of aristocrats and members of princely households, Joseph Conrad does not idealize their attire or ethical profile in the least. Conrad knows that their defining element is the continuity of fundamental choices–that inimitable and, in fact, inaccessible tenacity to those who do not share their multisecular ethos. The example of the officer protagonists in The Duelists is the perfect illustration of the continuity of a state of combat that qualifies them as what they are: warriors, military by vocation. Although almost as fragile and sometimes as capricious as any small (or large) bourgeois, they possess a strength that, when made visible, clearly distinguishes them from those unfit for greatness. Lieutenant Réal discovers, stunned, when he pushes Peyrol, that it was all “as though he had tried to shake a rock.”11 This is one of the best natural materials that can adequately describe them.

At the core of their beings resides that “old wandering self which had known no softness and no hesitation in the face of any risk offered by life.”12 Wanderers in a declining world, they reveal their true identity not through words, but through actions. Those who have ever seen a true prince, and not one of the worn-out ones whose scandalous exploits delight English speaking-world tabloids, know that he doesn’t need words. The simple fact of being, which is not the result of any Cartesian meditation, is the visible, palpable testimony of a person in their rightful place. That’s why, amid martial upheavals, they appear as poised as they do at the table serving tea at five o’clock. The emblematic figure that encapsulates the essence of a plausible hero is, without a doubt, Prince Roman.

Inspired, as in most cases, by a real historical figure, Prince Roman Sanguszko of Poland (1800–1881), the character in the Conradian novella is described in a way that brings him close to us, despite the distance that separates his heroic deeds from the grayness of our (post)modern lives. The author’s explicit aim is ultimate: rather than romanticizing princes as seen in fairy tales, he intends to present us with a real, living, and plausible prince in the flesh. First, the fairy tales:

Our notion of princes, perhaps a little more precise, was mainly literary and had a glamour reflected from the light of fairy tales, in which princes always appear young, charming, heroic, and fortunate.13

Then, the reality – absolutely plausible:

I had enough historical information to know vaguely that the Princes S. counted amongst the sovereign Princes of Ruthenia till the union of all Ruthenian lands to the kingdom of Poland, when they became great Polish magnates, sometime at the beginning of the 15th Century. But what concerned me most was the failure of the fairy-tale glamour. It was shocking to discover a prince who was deaf, bald, meagre, and so prodigiously old.14

Yes. This is how Conrad’s heroes are. Fallible, fragile, sometimes old, perhaps deaf and flawed. In a word, plausible. And yet no less epic. Sometimes they can drink quite heavily, like the metaphysical detective Philip Marlowe or like the equally metaphysical adventurer Rick Blaine in the movie Casablanca (1942). But always, it’s only to briefly anesthetize their moral sense, which, relentlessly, at the right moment, will help them make the right decisions and to adamantly fulfill them. By bringing them closer to us, Conrad strives to make us as familiar as possible with their values, his values. Which, I assure you, were never those of Romanticism or Modernism.

Thomas Mann, Doctor Faustus. The Story of a Novel. The Genesis of Doctor Faustus, Translated from the German by Richard and Clara Winston, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1961, p. 212.

Thomas Mann, Op. cit., p. 191.

The dedication is recorded in the superb biography authored by Joseph Conrad’s friend and translator, Gérard Jean-Aubry (i.e., Jean-Frédéric-Emile Aubry), titled The Sea Dreamer: A Definitive Biography of Joseph Conrad, Translated by Helen Sebba, New York, Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1957, p. 27.

The excellent essay signed by Mikołaj Gliński , “11 Reasons to Think of Joseph Conrad as a Polish Writer, After All,” is available online: https://culture.pl/en/article/11-reasons-to-think-of-joseph-conrad-as-a-polish-writer-after-all [Accessed: 26 October 2023].

The full text can be read here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/15679/pg15679-images.html [Accessed: 28 October 2023].

Published in Romania by Polirom Publishing House in Iași in 2008, Mircea Mihăieș’ monograph was translated into English by Patrick Camillar and published under the title The Metaphysics of Detective Marlowe: Style, Vision, Hard-Boiled Repartee, Thugs, and Death-Dealing Damsels in Raymond Chandler’s Novels, Lanham, Maryland; Plymouth, England, Lexington Books, 2014.

Rozovsky’s comments can be read online here: https://detectivesbeyondborders.blogspot.com/2010/12/conrad-and-chandler-marlow-and-marlowe.html [Accessed: 26 October 2023].

Joseph Conrad, Nostromo, “Author’s Note,” Wordsworth Classics, 1996, p. 1.

Joseph Conrad, Op.cit., p. 2.

Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim, Wordsworth Classics, 1993, p. 3.

Joseph Conrad, The Rover, New York, Doubleday, 1923, p. 67.

Joseph Conrad, Op. cit., p. 250.

The novella is available online here: https://fullreads.com/literature/prince-roman/2/ [Accessed: 28 October 2023].

And here: https://fullreads.com/literature/prince-roman/3/ [Accessed: 28 October 2023].