T.S. Eliot and detective stories

In addition to the authors of undeniable quality that readers of detective novels can enjoy, the genre’s library also contains literary critics of great stature. Edgar Allan Poe, Wilkie Collins, Émile Gaboriau, Arthur Conan Doyle, Gilbert Keith Chesterton, and Agatha Christie (to name only a few of the most well-known writers) are accompanied, perhaps surprisingly to some, by a poet and critic of the caliber of Thomas Stearns Eliot. He not only dedicated numerous reviews to mystery novels but also added valuable pages of literary analysis as well as a set of five rules that would allow the conception and writing of quality detective stories. For now, I leave the rules to the writers of such stories. What interests me here, however, are his main ideas regarding the crime fiction genre.

In an article entitled “Wilkie Collins and Dickens” published in 1927, he makes some observations which, although not necessarily very extensive, provided me with an excellent starting point for a discussion about the two authors to whom I dedicated this short essay. His comments focus on the development of the genre in England and the United States. In the case of the former country, he expresses his preference for Wilkie Collins: “The Moonstone is the first and greatest of English detective novels.” This categorical statement allows him to reveal a certain difference between the creations in England and those in the United States, a difference reflected in the art of character creation in the prose of W. Collins, on the one hand, and that of E.A. Poe, on the other.

The detective story, as created by Poe, is something as specialized and as intellectual as a chess problem; whereas the best English detective fiction has relied less on the beauty of the mathematical problem and much more on the intangible human element.

If in Poe’s detective fiction the emphasis is decisively on the logical component, challenging the readers’ intellect to follow the resolution of the mystery, in the case of Collins and other English authors, the emphasis falls on the mysterious, unpredictable dimension of the characters. In a simple but not necessarily simplistic formulation, we can say that while Poe’s reading predominantly engages the mind, Collins’s reading touches the hearts of the readers. In the context of English literature, Sherlock Holmes is an exception. Because he, though (almost) pure intellect, is, according to Eliot’s interpretation, a character whose humor balances the scale:

Sherlock Holmes, not altogether a typical English sleuth, is a partial exception; but even Holmes exists, not solely because of his prowess, but largely because he is, in the Jonsonian sense, a humorous character, with his needle, his boxing, and his violin.

This nuanced approach to the issue reminds me of the brilliant explanation from “The Frontiers of Criticism” (1956) that Eliot proposed in order to establish the guiding principle in poetry criticism. The role of the critic, in a sense similar to that of the poet, is “to help his readers to understand and enjoy.” Thus, it’s not just the mind and understanding, but also the heart and feelings. And, vice versa, not only the emotions and affections, but also the intellect. According to this fully justified vision, the characters in detective novels must embody not only logic and deduction but also metaphysics and intuition. With such support as that offered by Eliot, I can now confidently proceed to my own summary analysis of two of the most successful characters in the entire history not only of detective fiction but of English literature as a whole.

Sherlock, the dialectician

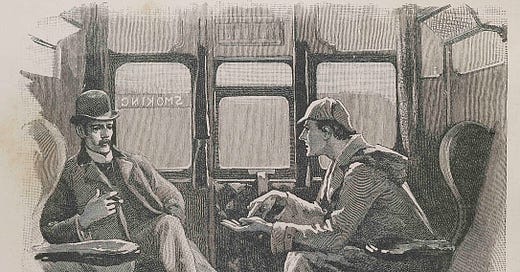

The exegesis dedicated to the character created by Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle makes its complete coverage impossible. I don’t know if in this vast library there exists one or more volumes in which, before me, a critic or literary historian has noted that Sherlock Holmes embodies, probably involuntarily, a brilliant form of popularizing Aristotelian-Scholastic logic. Indeed, in my opinion Holmes is a perfect dialectician. He never misses an opportunity to express not only his aversion to superstitions and, eventually, the religious perspective on things, but also his reservation towards any form of knowledge that does not involve deduction. For him, induction and intuition are out of bounds. If facts are necessary, the ability to establish the connections of detective syllogisms that lead from premises to conclusions represents the supreme form of knowledge. In a certain sense, he is a perfect embodiment of the positivistic, rationalistic spirit of the Enlightenment age.

Very interestingly, this primacy of reason is accompanied by traits that imply not only the Jonsonian humor noted by Eliot. Alongside this dimension, which endears him to readers, there are behaviors that seem to suggest the dark secrets of his geometric soul. I’m not sure if I can say that Sherlock would be an ego-maniac, but a certain kind of egocentrism generates reactions—let’s call them—extravagant. This is not new in Doyle’s characters. Despite the differences from the occupant of the apartment in Baker Street, the notorious Professor Challenger from The Lost World is also extremely concerned with asserting the infallibility of his intelligence. In the name of a higher understanding, he never misses an opportunity to underline the quality of his theories. This wouldn’t necessarily be reprehensible if it weren’t accompanied by a hint of contempt for other members of the scientific community or for the poor journalists fond of sensational interviews.

On the other hand, in the case of Sherlock Holmes, the profound motivation behind his actions, which indeed manifest remarkable courage and tenacity, is not necessarily altruistic. If in the detective novels of Poe, Eliot mentioned their similarity to chess problems, Holmes seems to be primarily animated by the ambition to solve new puzzles just to prove—to himself and to others—his abilities. Both the character embodied by Jeremy Brett in his films and the no less remarkable one created by Matt Frewer capture his undisguised pride very well.

As time passes and the opportunity for a new display of his intellectual qualities does not arise, Holmes falls into a state of torpor, bordering on depression. The atonal violin music he invents ad hoc, the gruffness of his displayed appearance without gentleness, the lack of communicability, and sometimes even the intoxication with fashionable drugs of his time, turn him into an anti-hero who vaguely resembles Raymond Chandler’s almost-alcoholic detective Philip Marlowe. Of course, we cannot expect a modern author to propose to readers a detective with the traits of a saint. By the way, could such a thing be possible?

Father Brown, the metaphysical hunter of souls

Gilbert Keith Chesterton believes so. If it had remained merely at the level of a simple aspiration, such an answer might have seemed only daring. Father Brown, one of the most beloved and popular detectives ever to exist, proves that Chesterton achieved the impossible. An indication of this extremely difficult, extremely rare success is the testimony of the same Thomas Stearns Eliot:

When I am considering Religion and Literature, I speak of these things only to make clear that I am not concerned primarily with Religious Literature. I am concerned with what should be the relation between Religion and all Literature. Therefore the third type of ‘religious literature’ may be more quickly passed over. I mean the literary works of men who are sincerely desirous of forwarding the cause of religion: that which may come under the heading of Propaganda. I am thinking, of course, of such delightful fiction as Mr. Chesterton's Man Who Was Thursday, or his Father Brown. No one admires and enjoys these things more than I do; I would only remark that when the same effect is aimed at by zealous persons of less talent than Mr. Chesterton the effect is negative.

Firstly, we see that Eliot does not hesitate to discuss Chesterton’s apologetic intention—who certainly is one of those who aim to “forward the cause of religion.” However, he does this without becoming moralistic or, even worse, a propagandist of the religious cause. The second thing highlighted by Eliot’s statement acknowledges the difficulty of such an undertaking. Without immense talent and literary experience to match, any writer who dares to tread this narrow path is doomed to failure. But how did Chesterton manage what very few attempted—and even fewer succeeded?

Firstly, Chesterton is an authentic master not only of paradox, often remarked upon, but also of incarnate metaphor. He has a profound understanding of how the virtues of humility, courage, counsel, and ultimately wisdom can be expressed through poetic and literary images and symbols. The balance of shadows and lights in Father Brown’s personality seems to resemble that of an anonymous, unnoticeable parish priest who, in moments of grace, behaves like Saint Philip Neri: joyful without being frivolous, optimistic without being superficial, attentive to details without being scrupulous, and above all, motivated by a profound charity towards others. If the thirst of Christ on the cross can be understood as representing, with dramatic intensity, God’s thirst to save souls, we can say that Father Brown is animated, like his author, by the same thirst. He not only wants to catch criminals and punish them, but also to gather scattered sheep from the inner wolves of vices and misjudgments. This is the main motivation of the Chestertonian hero.

Unlike Sherlock Holmes, the unbeatable logician, Father Brown does not seek to prove anything. He has no need for applause from the public or for the self-satisfaction of an ego eager to reveal its excellence. Discreet and unassuming, he shines just enough through heroism, intelligence, and fervor when he can lead a lost soul out of the labyrinth of sin.

Despite appearances, his main knowledge is not deductive, logical, or rational. I don’t mean to say that he lacks any of these, but rather that what he possesses is much more. It is a guidance resulting from the prophetic gift received at baptism, which he actively exercises under the influence of that Inner Master (or Teacher), spoken of by Saints Augustine and Thomas: the Holy Spirit. In short, Father Brown is visibly inspired from the invisible, paying homage to a knowledge based on a form of intuition far superior to the capacity of reason. He is more of a metaphysician—or even a mystic—than a logician.

Like the genius doctor who diagnoses the patient at first glance, without consulting him, Father Brown seems capable of detecting the illnesses of souls caught in the web of sins as well as Saint Padre Pio. Although in most cases he appears to act, like Sherlock Holmes, relying solely on deductions, if we refocus the distance from which we view his actions during reading, we will realize that, in fact, he is following the lost sheep—the culprit—carried by an unseen spirit whispering in his ear what only the graces of the holy priesthood allow him to see. I spoke of ‘refocusing’ precisely to indicate the multiple angles that the detective novels of his friend Hilaire Belloc allow. Skeptics, agnostics, and unbelievers may see Father Brown as a skilled deductive sleuth, while Christians may find in him a true metaphysical shepherd. This fortunate ambiguity offers very different readers the chance to come into contact with the demands of Christian holiness, conveyed through the mediation of a literary character who can delight even such a demanding critic as T.S. Eliot.

I have been interested in reading the Father Brown stories ever since I saw a film based on them. Which ones would you recommend? Are there also any Agatha Christie mystery novels you would consider good to read for a youth?